The challenge

Overleaf was scaling up fast, and so was its product team. Product managers, designers, and analysts were being hired and growing in the company. How could we support this growth in a systematic, yet flexible, and fair way?

My role

As Head of User Experience (UX), I worked alongside the Director of Product and the Head of Analytics — the three functional product leads. My role was to lead the project (mostly ensuring progress and pace) as well as to flesh out the details of the career ladder for UX.

The foundations

Although we weren’t entirely sure of the final shape of the ladder, we had a few ideas — almost like values we’d like to embody.

The first one was the notion that we wanted a tool to guide and foster growth conversations, not a checklist. We didn’t want something to say “nope; you haven’t ticked this one, so you can’t progress any further”; we wanted something that invites discussion and provides direction.

The second one was thinking about the commonalities between the three functions (product management, UX, analytics). We weren’t entirely sure whether we’d end up with a common career ladder for the entire product function, a common trunk of competencies, or just some shared elements. We were sure, however, that we wanted the ladder to reflect the blurred boundaries and interdisciplinary nature of our jobs.

The third one was ensuring equal progression opportunities for everyone, regardless of their career preferences. Specifically, not everyone wants to be a manager; yet this shouldn’t prevent someone from growing in their role. We wanted a career ladder that provided clear paths for specialisation, both as an individual contributor and as a manager.

Starting with research

Always keen not to reinvent the wheel (and acknowledging that many others, much smarter than we are, have tackled the same problem), we began where any reasonable person would: by looking at what others have done. Luckily, someone made our job easier by creating a fantastic website listing many career progression frameworks: https://progression.fyi (thanks!). We explored many, including Spotify, GitLab, and the UK Government’s Digital Service. This allowed us to understand the patterns, but also the breadth of approaches out there — there’s a lot of variability when it comes to granularity.

Mapping what we know

As leaders, we had a good grasp of what our teams were doing and what our functions entail. To start organising our thoughts, we held weekly work-sessions — asynchronous work is amazing, but sometimes you need to block some time in your calendar and work with others (holding each other accountable) to ensure progress.

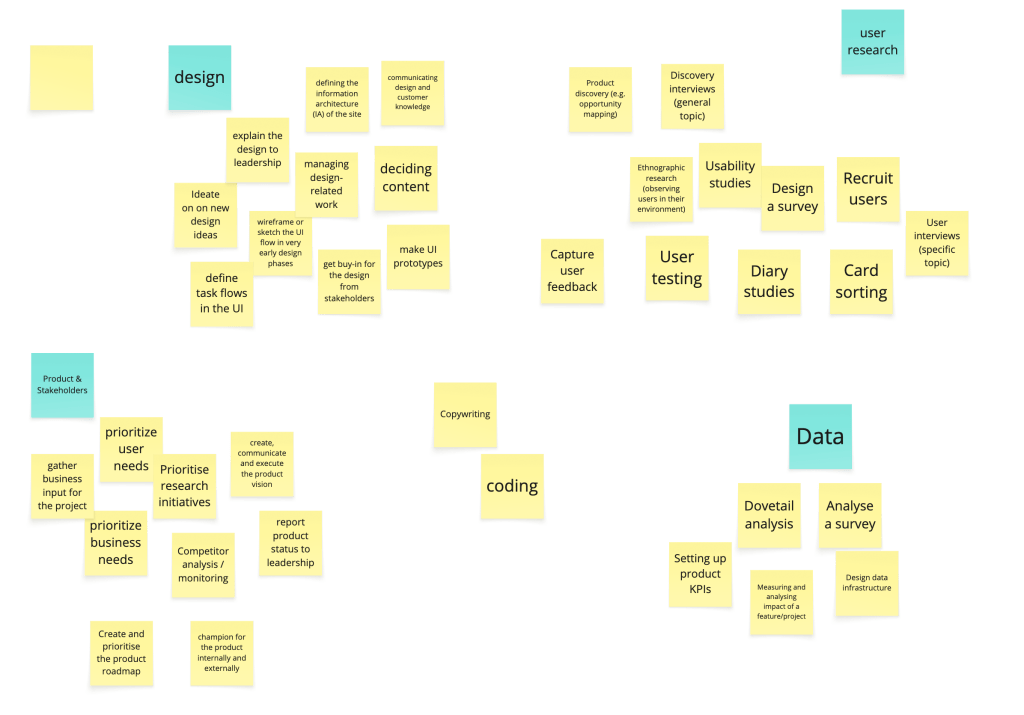

We started with simple post-its, just writing down all the work activities we and our teams were performing.

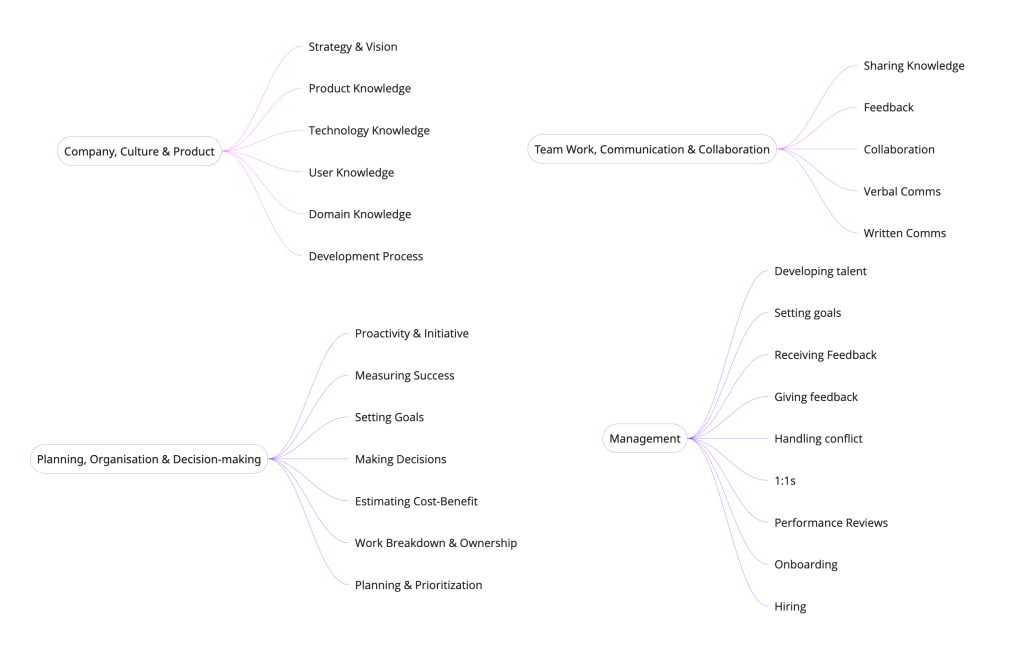

From that, we have started drafting what competencies

We have also started fleshing out what a common trunk of competencies could look like — although we ultimately did not implement it, it certainly allowed us to be more explicit about the commonalities.

The reality check: team workshops

Almost as a counterpoint to the section above, we were also acutely aware that this needed to be a collaborative effort with the whole team. They would understand better than we do what fair and useful looks like. They would also be much closer to the day-to-day work, therefore would be able to complement our vision with theirs.

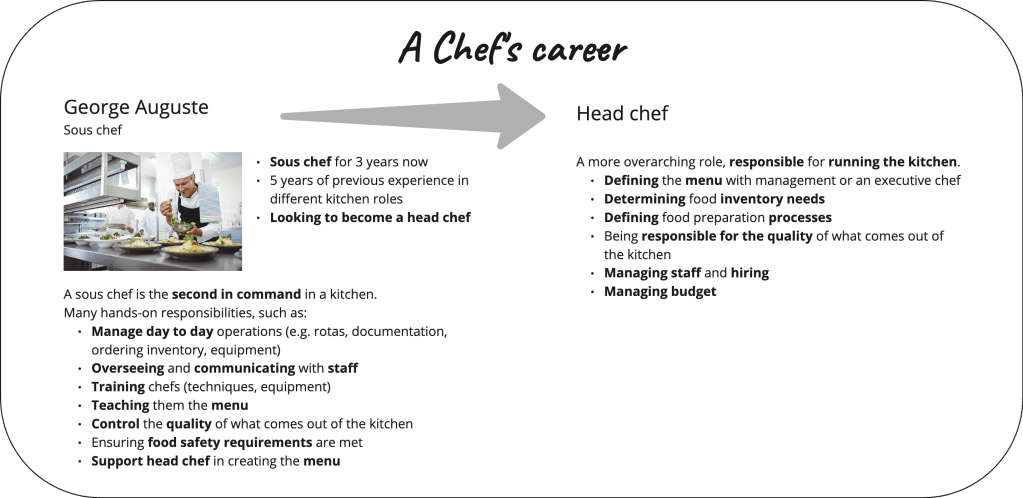

The first workshop we ran was a values workshop. We wanted to understand what fair looks like to our teams. For this, we’ve created a scenario detached from our daily realities: George Auguste, a sous chef wanting to become a head chef. We then workshopped with the team around two main questions:

- What can the company do to support George in achieving his goals?

- What can George do to achieve his goals?

The message we got from the team was that we should:

- Be honest about available opportunities: Don’t let people work toward roles that don’t exist. If there’s no head chef position coming up, say so. People deserve to know what’s actually possible versus what’s aspirational.

- Define what progression actually means: Write down what distinguishes junior from senior from lead. Include both IC and management tracks.

- Create safe spaces: Let people try head chef responsibilities without full accountability for failure. Shadowing is a good start, but people need hands-on experience with mentoring support to genuinely develop.

- Move from conversations to concrete plans: Set specific goals with real timelines and regular check-ins on progress.

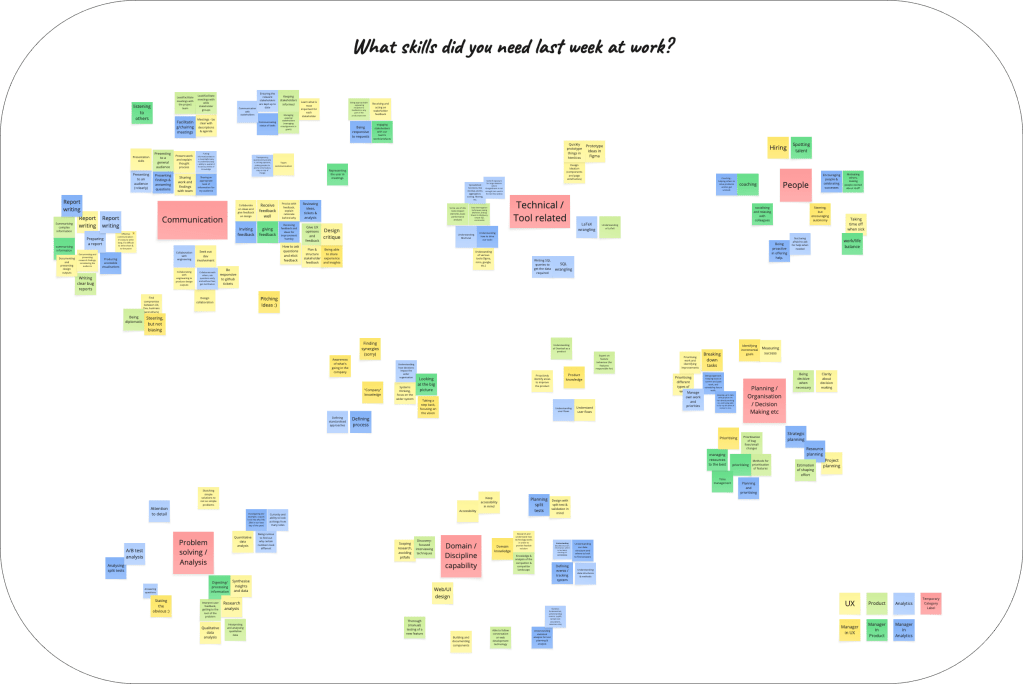

The second workshop was a competencies workshop. We essentially asked the team first to brainstorm any competencies they needed (or even just activities they had done), and then worked on clustering them, discussing, etc.

The (draft) career ladders

Equipped with all the insights from the workshops and our previous explorations, we got back to work with the goal of creating a first draft version of the career ladders.

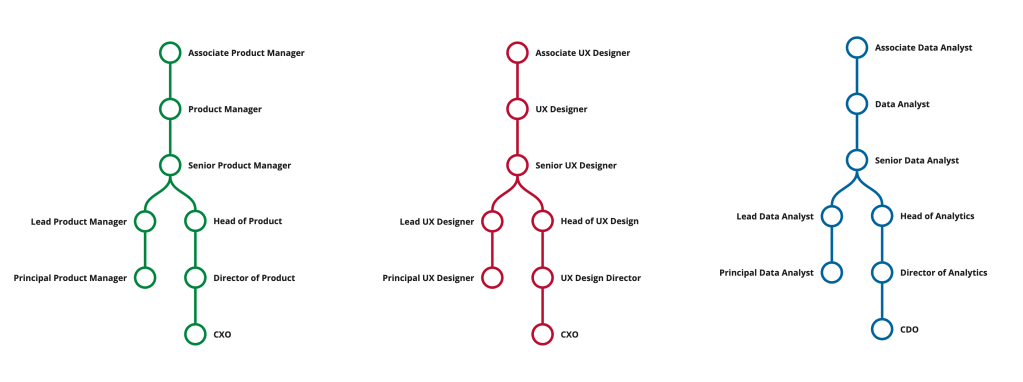

Y-shaped ladders & levels

The first step was solidifying the topology of the ladders. We agreed that we wanted consistent levels and to allow people to progress without necessarily taking on line management responsibilities.

We have established a progression from Associate to Principal/C-level and created consistent names for these levels across the three disciplines. After senior, the career ladder splits into two separate branches: a specialised IC path and a management path.

Identifying the competencies

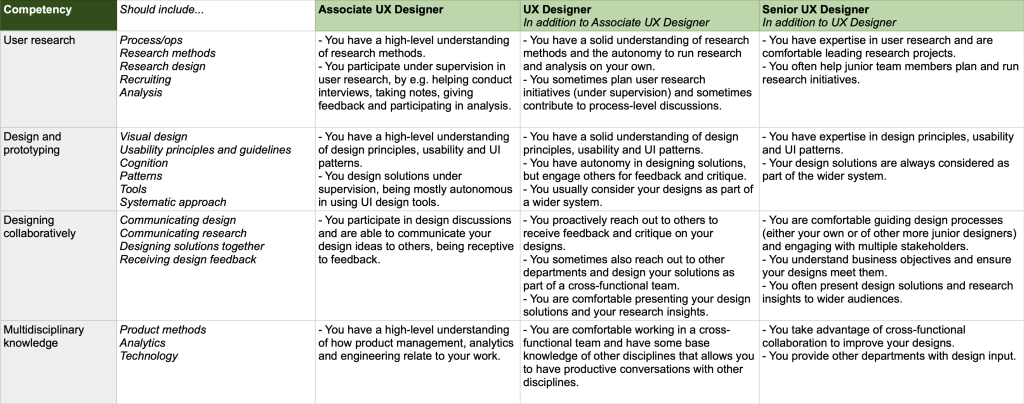

We have then finalised the list of competencies for each of the three ladders. We opted not to implement a common trunk, but instead to have some shared competencies (some completely shared, while others are shared but with different expectations based on the function — e.g., we should all be able to analyse data, but obviously the expectations from an analyst are higher).

Deliberately, we kept the number of competencies low and manageable. We thought it was best to start small and add to the ladders later, if necessary — this acknowledged the “draft” nature of this first version, but also mitigated the risk of overwhelming team members.

Mapping skills to levels

Equipped with levels and competencies, the next challenge was to describe what the expectations were for each competency, at each level. For instance, what do we expect from a Senior UX designer when it comes to Design and Prototyping?

As mentioned before, we wanted the ladders to be tools that support progression conversations rather than mere checklists. To achieve this, we’ve worded the “descriptors” (the term we used to define the expectations for a given competency at a specific level) with some deliberate ambiguity and latitude to explore.

Outcomes

With a first draft in hand, we trialled the career ladders with team members. The feedback we got back was essential — we revised several descriptors where the ambiguity was too much (hindering rather than helping) or where we’d simply failed to capture important aspects of the work.

We’ve used the ladders to guide the subsequent annual performance conversations. They’ve given both managers and team members a shared language for talking about growth and progression — which was exactly what we hoped for.

More recently, as Overleaf went through a reorganisation as part of Digital Science, we’ve also had the chance to contribute our learnings more broadly. Digital Science established a centralised product function, across all products, in a matrix-style organisation. We’re now incorporating these lessons into Digital Science-wide career ladders, helping shape how we think about supporting growth across the organisation.