Tl;dr: I vibe-coded a weightlifting workout generator app using AI for the actual workout generation — try it out at https://workout-generator.paulojreis.com/. Code available at https://github.com/paulojreis/workout-generator

I’ve been using AI extensively at work for prototyping, and wanted to explore vibe-coding for end-to-end product development: building something that could be maintained and deployed, not just a throwaway prototype. My specific goals: experience a fully AI-assisted workflow, try new tools (particularly Figma’s MCP server), and build something where AI is a core feature, not just the development method.

By “vibe-coding”, I mean building software through conversation with an AI, where you describe what you want (the so-called “vibe”) rather than writing the code yourself. It’s effective when you understand what you need conceptually, but don’t know the exact APIs or implementation details. The AI fills in those gaps while you steer direction. The trade-off: you move faster, but with a shallower understanding of everything you’re implementing.

The app

I’m not a fan of user stories, but here’s one: as a business traveller, I want a quick workout that I can perform in 30 minutes with bodyweight and dumbbells only, because that’s all the equipment my hotel gym has, and I don’t have a lot of spare time.

Many workout apps (and workout plans) assume you have access to all the necessary equipment. And they are not adaptable to other constraints you might have, such as goals or available time.

So this is what I wanted to build: a weightlifting workout generator based on a set of common end-user constraints, powered by an LLM. I spend a lot of time in the gym, so I understand this problem as a user.

Why LLM-powered? I could generate random workouts from an exercise database, but exercise selection, ordering, volume, and rest periods are chosen intentionally when planning effective workouts. An LLM can analyse exercise science literature, distil it into guidelines, and then generate workouts following those principles.

Tools

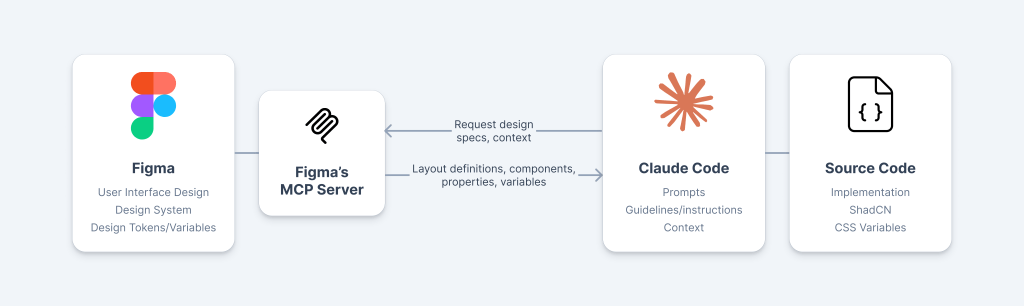

From a design and development perspective, I have used Figma and Claude Code, connected via Figma’s MCP server, which provides design context to Claude Code (more details below). This was one of my learning goals: to explore effective strategies to bridge design and development, taking advantage of Figma’s MCP server.

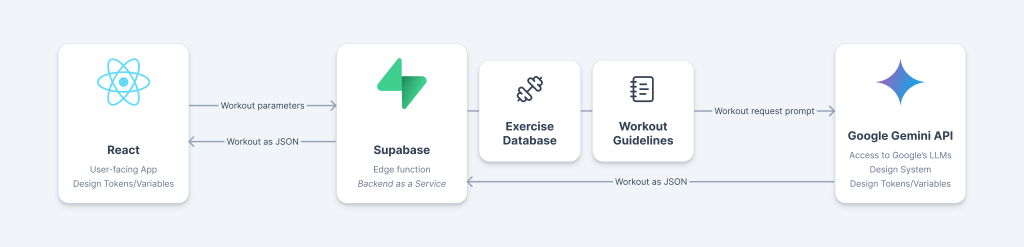

From a technical architecture perspective, I wanted a serverless app with minimal backend functionality to integrate with an LLM.

- Frontend: React with Vercel deployment (which led to Vite as the build tool). Component library: ShadCN.

- Backend: A Supabase Edge Function connecting the frontend to the LLM. Think of it as a small, contained piece of backend functionality offered as a service.

- LLM: Google Gemini’s API, specifically the 2.5 Flash-Lite model. The generous free tier meant I could fit in maximum requests within the limits.

UI and frontend

As mentioned above, one of my goals was to explore ways of bridging design and implementation.

When you have a well-defined design system (as well as its foundations), you have essentially a shared language between designers and developers. A “primary button” means precisely the same thing in design and code — same component, same behaviour, same properties. A shared language streamlines communication and reduces ambiguity; there’s no need for translation between design and code anymore.

This shared language is something you get by having a design system, one that both designers and developers adopt and co-own. But we can take this a step further. It’s great to have designers and developers unambiguously refer to the same colours and components, but what if we could automatically pipe that information from design to code? MCP (Model Context Protocol) enables us to do exactly that.

MCP is an open protocol/standard that allows AI tools (like Claude Code) to connect to and read from external sources (in this case, Figma files). With Figma’s MCP server running, Claude Code can read the design file directly, eliminating the need for manual handover and specifying design details in prompts. A developer doesn’t need to open Figma to check spacing values or find the correct component variant. The designer doesn’t need to write specs documenting which colours or tokens to use. The context is already there, accessible when needed.

To enable this seamless workflow, I’ve decided to use ShadCN as a proto-design system (itself built on top of Tailwind CSS) — this ensures that whatever components (and even values, such as colours) used in Figma are also available in the frontend. Then I enabled Figma’s MCP server.

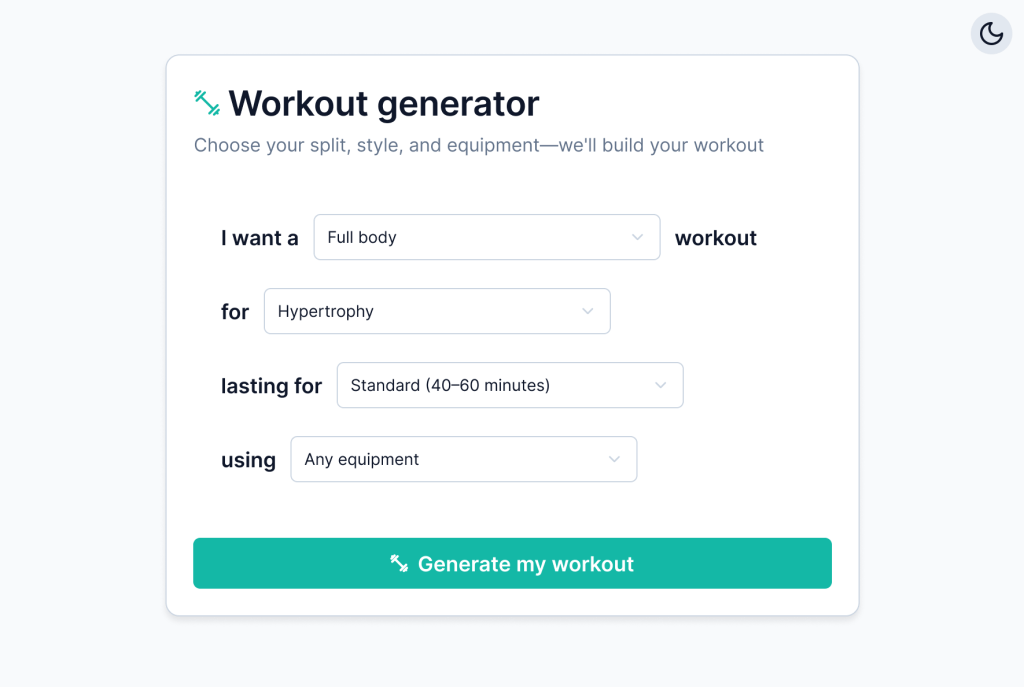

For the UI itself, I have developed a simple “sentence-based” UI, which allows the user to select:

- What they want to work out (full body, predefined sets of muscles, or combinations of individual muscles)

- What’s their goal

- The duration of the workout

- The equipment they’d like to use

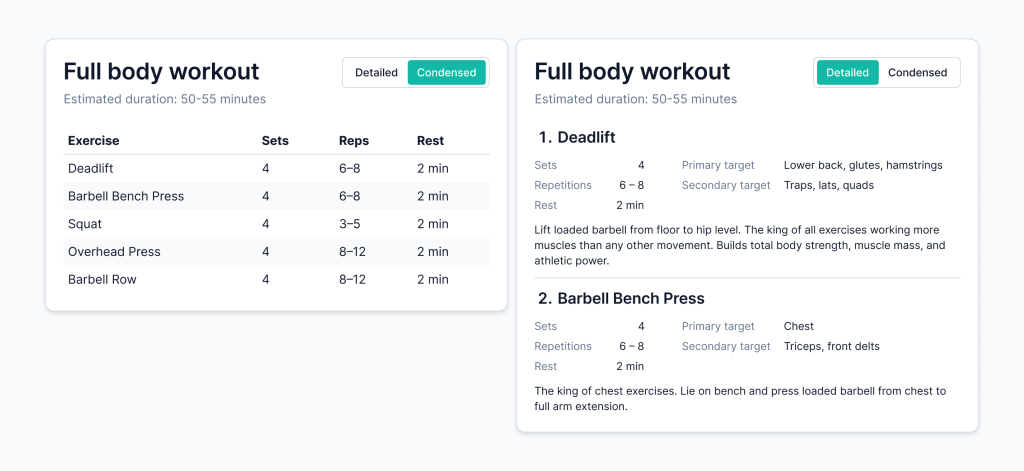

After configuring their choices, users can generate their workout. I’ve opted to provide two toggleable layout options: one with a lot of detail (e.g., on exercise technique) and another that is much more concise.

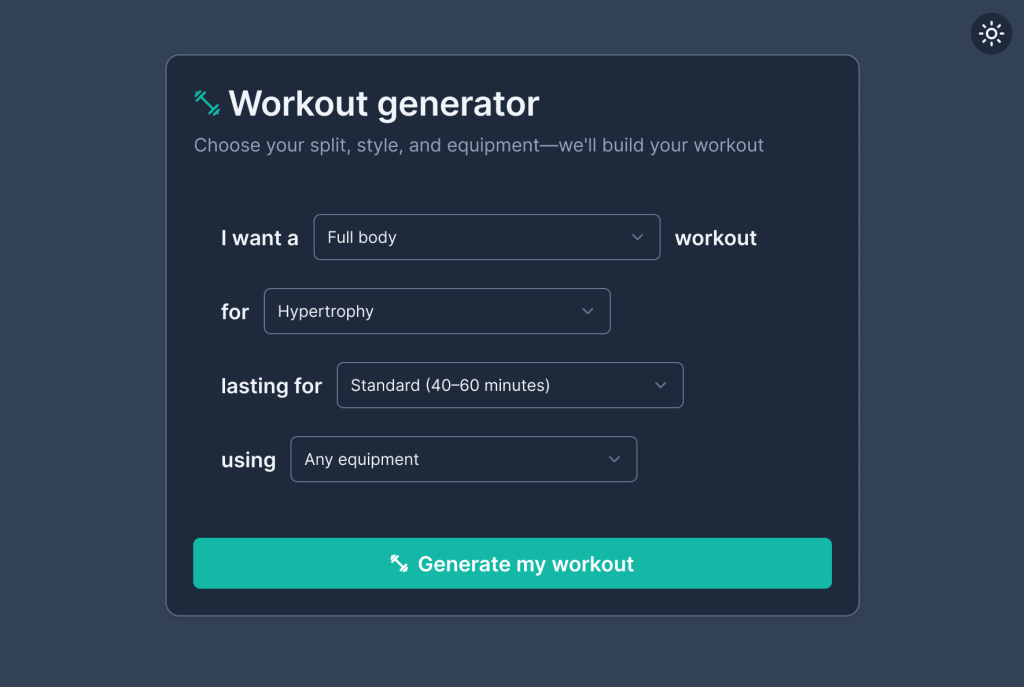

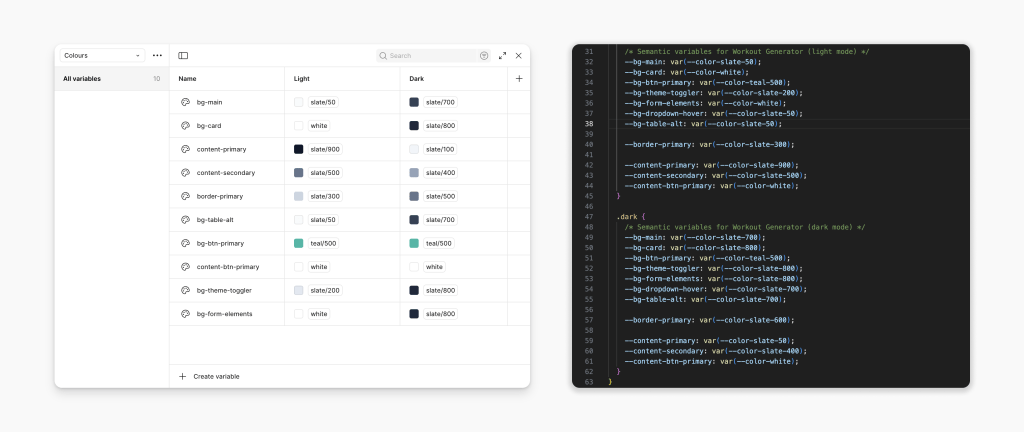

I’ve used a very simple palette, with teal as the accent colour. All of these choices were codified as Figma variables/design tokens, themselves pointing to Tailwind variables. This made it trivial to implement a dark mode as well (using Figma’s variable modes feature).

For the frontend itself, I’ve started with Claude Code, requesting that it bootstrap a React App, assuming Vercel deployment (which I believe led it to use Vite as the frontend tooling framework — a great choice), and using ShadCN as its component library, just as in Figma. It worked perfectly.

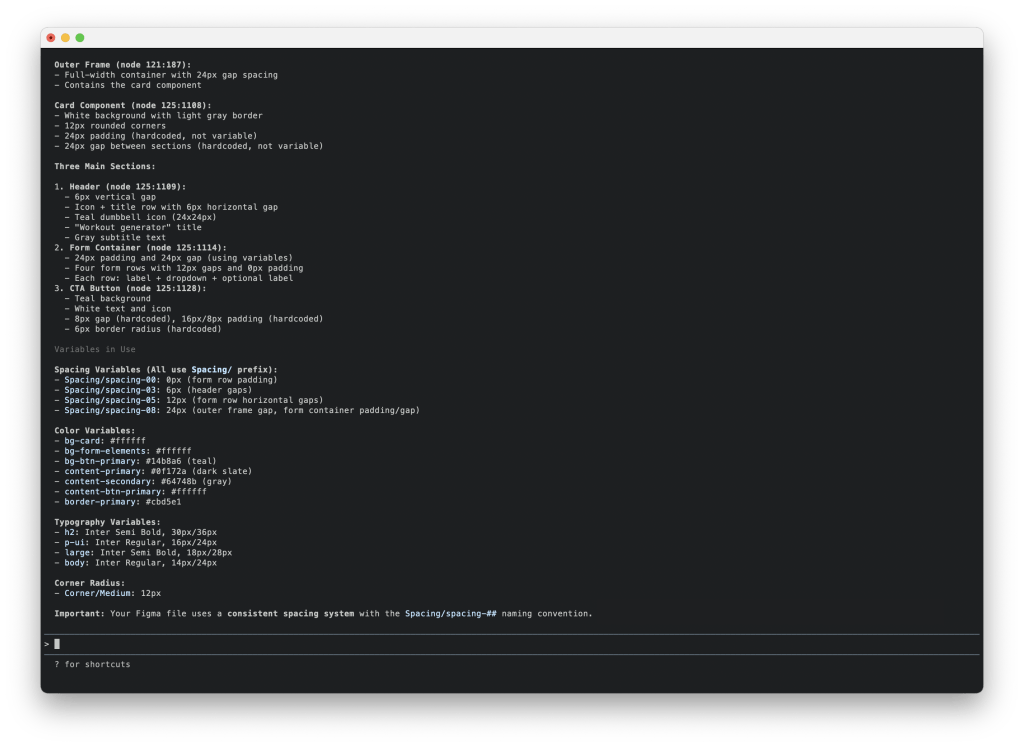

After bootstrapping, I had the moment that validated the entire workflow: I asked Claude Code to analyse my Figma file and extract its variables. The Figma MCP server was already running, and everything just… worked. Claude Code accurately described the UI, the variables in use, the components — all the design context was passed through automatically. No specs, no manual translation.

Having validated the MCP as a bridge between Figma and code, as well as its accuracy, I’ve started working with Claude Code to recreate the foundations I established in Figma: design tokens/variables and ShadCN as a component library.

With the app’s frontend bootstrapped and using the same language I had used in Figma, I began implementing the user interface. This went well, but not perfectly. I was impressed, but also acknowledged some of the system limitations.

For the most part, Claude Code did the right thing, implemented the interface with the same components I’ve used in Figma, and filled in the gaps appropriately. Every now and then, it would make odd choices: once it implemented a custom dropdown with inline styles instead of using the ShadCN Select component I’d explicitly used in Figma. Another time, it duplicated button styling code across components rather than using the CSS variables we’d defined.

Again, it’s not perfect, but still quite impressive. For the most part, it works well — and you can mitigate issues 1) with clear project-wide instructions (in the CLAUDE.md file); and 2) with descriptive, specific prompts (i.e. minimising the amount of guessing the model has to do).

Backend and AI functionality

As mentioned above, my goal was to utilise an LLM to generate workouts, and this was the only planned backend functionality: to take the user-defined workout parameters as input and request a suitable workout to be generated by the LLM.

For the workout generator, I have created two artefacts for the LLM to take into account:

- An exercise database, with a specific schema (to match the information needed to generate the workouts, e.g. targeted muscles, as well as the information I wanted to display to the user)

- A document outlining exercise selection and workout planning guidelines for the LLM to use and consider when generating the workouts.

These two artefacts were generated and tested with Claude (the chatbot, not Claude Code).

For the actual implementation, I started by configuring both Supabase (for the edge function) and Google’s Gemini API (for the LLM), and generating the necessary API keys/tokens. I then used Claude Code to start coding the edge function as well as the Gemini configuration and prompt.

This is where Claude Code really shined. My requirements were roughly:

- A stateless edge function.

- Invoking an LLM, with a well-defined prompt with parameters, and ensuring a response in a machine-friendly format (JSON, with a specific schema).

- Avoiding hallucinations (LLM must not invent exercises; it also must respect the constraints — no barbell suggestions if the user doesn’t have access to one)

- Prompt caching (the app is on Gemini’s free tier and the prompt itself was fairly large, including the exercise database and workout planning guidelines).

I knew conceptually what these requirements meant and why they were important, but I wasn’t familiar with the specifics, particularly when it comes to implementation. I couldn’t implement this on my own without spending a lot of time reading through Supabase’s and Gemini’s API docs (and experimenting). This is, I think, the sweet spot for vibe-coding: when you know what you want (beyond a simple description of functionality) and are able to steer the model meaningfully.

Again, as with the frontend, it all felt quite impressive, but not perfect. As an example that illustrates my point above (it’s best when you steer the model), Claude Code required some explicit prompting to avoid typical API key/token pitfalls (such as exposing the keys on the frontend or in version control systems).

As a final note on implementation, Claude Code was very helpful with deployment. As mentioned above, I had a conceptual understanding of what I wanted, but I didn’t know the exact implementation details.

- The edge function to be deployed with Supabase

- The app itself to be continuously deployed with Vercel, linked to the GitHub repo

- All available at a subdomain of my own personal domain

Claude Code helpfully assisted me with each of these, effectively filling in my knowledge gaps (or actually driving things based on my input).

Conclusions

After building this project, I have different takeaways for designers, developers, and everyone navigating the responsibility questions these tools raise.

For designers

For designers, assuming you have a shared language with your developers (design tokens/variables; a design system), and design and implementation closely match as a consequence of this shared language, then something like Figma’s MCP seems like the next logical step. The shared language itself is a massive efficiency driver; if you add in the MCP, you’ll significantly reduce your manual handover needs (allowing you to focus on discussing what matters).

Depending on how comfortable you are with implementation, Claude Code might also be helpful if you need to bring your design to life (either because you need to use it to understand how it feels, or because you need an artefact for testing with users, or even because you might want to step into the world of development). It’s worth noting that there are other options that I feel are friendlier for designers looking to prototype (e.g., Lovable, Figma Make). Claude Code is, I think, best suited to work with existing codebases or to assist you in creating production-ready code.

Outside of this experiment, I generally found “vibe-coding” very useful for prototyping. Often, I find Figma’s (and similar tools’) prototyping capabilities to be very limiting — these are static prototypes; everything needs to be built manually (or close), making any richer, dynamic, interactive flows hard to implement. If you want to prototype a search experience with dynamic results based on your search query, a static prototype won’t cut it. If you then want to take this a step further and prototype, e.g. filtering (which would depend on search results), then you really need something more dynamic. Using “vibe-coding” allows you to build much richer interactive prototypes, often allowing multiple user paths with live, dynamic data — these will yield more meaningful and reliable test results (because testing conditions are closer to actual, real-world usage).

For developers

From an implementation standpoint, I think Claude Code is a great accelerator. I knew I needed a backend-as-a-service, and actually only needed one high-performance function. I also knew that a good technical solution for this was an edge function. I had never coded one, but understood it conceptually — AI allowed me to implement it without learning everything from scratch and going through all the docs.

Similarly, I also knew that I needed to use an LLM in a very specific way: with a strict yet configurable prompt, with caching, and with a strict, machine-friendly output (in JSON format). Again, I understood all of this at a conceptual level, but it would have taken too long to learn how to actually implement it.

One of the trickiest aspects to manage is how specific your prompt should be. I found that being precise helps, but it’s a slippery slope — you can always be more specific and explicit; however, if you specify every little decision, your efficiency gains are lost. For the most part, Claude Code seemed to understand what I wanted and filled in the gaps adequately. Figma MCP helped with this: most of the time, I didn’t have to specify which colours or which components to use; Claude Code would get that information from Figma through the MCP. Yet, sometimes, and seemingly at random, it would simply ignore that information altogether and implement something similar, but with e.g. different components.

This leads me to another aspect I struggled with: Claude Code’s behaviour sometimes felt nondeterministic. I couldn’t pinpoint why—is it the context window limit? Prompt ambiguity on my part? Model temperature settings? Some combination? Sometimes it would impressively infer exactly what I wanted; other times it would ignore previous instructions entirely and do something silly. I’m still working through what triggers each mode, but I also appreciate that this is perhaps the exact same capability that allows these models to fill in the gaps, come up with creative solutions, etc. In practice, I’ve learned to review every change carefully and maintain explicit project instructions, treating the nondeterminism as a feature to manage rather than a bug to fix.

The responsibility question

Here’s the uncomfortable part: we can now prototype and ship much faster without fully understanding what’s happening under the hood. That’s powerful, but risky — as the saying goes, “with great power comes great responsibility”.

The question isn’t “did you read the documentation?”, or “did you write every single line of code?” — we’ve never expected developers to read every piece of documentation, or write every line of code (in fact, they shouldn’t). The real question is: do you understand the failure modes, security implications, and edge cases of what you’re implementing? Can you reason about what could go wrong? Would you know where to look when (not if) something breaks?

Most people would agree that fully relying on AI without understanding what’s happening is wrong. At the other end of the spectrum, most would also agree that building everything from scratch isn’t a realistic expectation (and leads to all sorts of problems — there are many good reasons why we don’t like to reinvent the wheel). Where things get fuzzy is in the messy middle. For this side project, all the vibe-coding was probably fine. But where’s the line? At what point does “I vibe-coded this feature” become irresponsible? When it’s customer-facing? Handles payments? Processes personal data?

This isn’t fundamentally new—we’ve always had developers copying StackOverflow snippets they don’t fully understand. What’s new is the scale and (lack of) friction — and these variables matter. In a couple of afternoons, I integrated 10+ technologies that each would have required meaningful learning time. A designer with no coding experience could build a fully interactive prototype in the same timeframe. This is too tempting (and too valuable) to ignore. I can’t offer a specific rule or guideline to answer the question of how much we should understand what we build. For a side project, or a prototype you’re testing with a few users, you probably don’t need deep understanding. But what if it’s a production feature thousands of people will use? Or a business-critical scenario? Then I’d argue that you need to be able to defend your choices, to understand the trade-offs you made (either explicitly or implicitly) and ultimately to maintain the code that you may or may not have written.